Article/Video: "Steve Gerber Is Smoking"

Here's my published 1975 interview with Steve "Man-Thing" Gerber, the Marvel Comics writer then already on a hot streak. I was a 20-year-old comic superfan, and dug the convo muchly. Here's the piece.

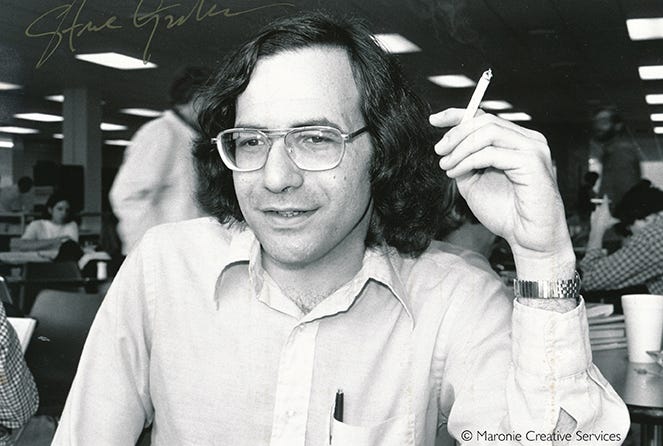

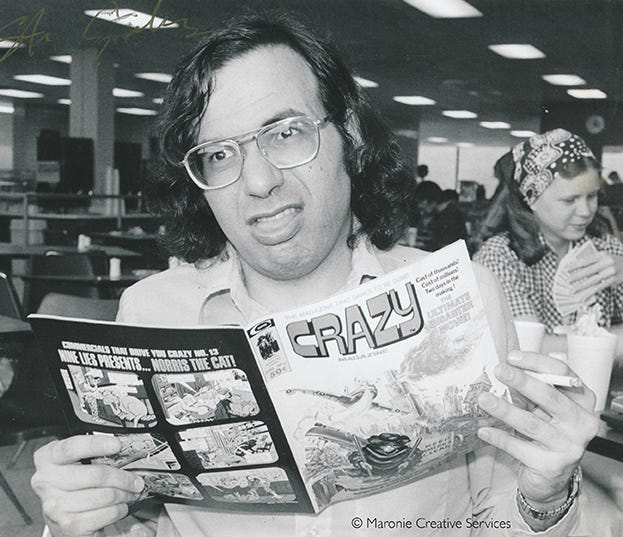

This interview first appeared on July 1, 1975, in The UMSL Current, the student-run newspaper of the University of Missouri-St. Louis, which Steve Gerber attended in the early 1970s. Photos by Sam Maronie © Maronie Creative Services

A man groans…

…because his female companion admits she is only sixteen; he’s legally kidnapped her.

A young poet recalls 1967 – “the year Sgt. Pepper came out” – and a confrontation with a military scientist.

A ghetto catches fire at the hands of racist militants.

A Southern bigot sheriff pursues his quarry, a Black man, through a swamp.

These scenes are from neither novels or screenplays – but from comic books.

The author is Steve Gerber, who was born in St. Louis and raised here until he left for Manhattan. A few years ago, Gerber was at UMSL, picking up credit hours. A few days ago, he was in New York, picking up the comic book industry’s equivalent of the Oscar Award for being “Best Dramatic Writer” in the field.

Now in possession of a “Shazam” award, named for Captain Marvel’s mystic cry and given by the professional association of comic book writers, artists and editors, Gerber has seemingly found ample direction for the creative energies he honed here in the Midwest. The award is no small honor, nor slightly deserved: the 28-year-old writer has produced some of the most sophisticated, powerful and respected comic book stories to see print in recent years.

For a man who frequents galaxies and dark swamps from behind his typewriter, Gerber seemed oddly at home in the UMSL “snacketeria, “which he recently visited for an interview with The Current. Sipping coffee, the bright-eyed Gerber was like a comic book himself: a combination of the somber and absurd.

"Good books that also happen to be comic books"

“There are those who say the comic books are candy, and I can’t disagree with that entirely,” Gerber says. “This is no substitute for reading good books, you know. That’s not to say that they can’t be more than candy. That’s not to say there can’t be good books that also happen to be comic books. But I don’t see just stopping and saying, ‘Well, because this is a comic book, it can’t be anything else.'”

“It is a struggle to do something responsible in a media often justifiably attached for shallowness and banality.” The Gerber impish grin then appears. “Like the audience. The letters we get! There’s an example I like to use…

“Suppose Geoffrey Chaucer got fan letters"

“Suppose Geoffrey Chaucer got fan letters, right? ‘Dear Geoff: Really enjoyed Canterbury Tales. Far out, man. Would have liked it a lot more, though, if you hadn’t put so much of your own opinions in it. Well, till next ish, I choose Chaucer. A dedicated fan.”

The “own opinions” he defends are abundant in Steve Gerber stories, and it is this strong thematic undercurrent that strengthens Man-Thing, Son of Satan, The Defenders and other comic book titles Gerber writes. In an industry populated with superhuman beings and fiery monsters, Gerber stages his stories with deep, human characters in intensive, often profound interactions.

The melodrama and the supernatural elements are there, too, of course. But those the blood and bones of comic books’ concerns, and have been in the complex four-decade history of America’s most unique art form.

The market is substantial: millions of comic books reach their readers every week, and those readers include a sizeable and increasing portion of adults, including many college students.

The prime market is, of course, still children. And that’s why comic books have self-inflicted chains for years, absorbing ridicule and scoff. Some writers, however, realize that children’s reading can be children’s literature, as well – that the superheroes who dominate the extremely visual media are actually part of modern epic mythology. And some writers – like Gerber – aren’t afraid to use those myths as a commentary on the current Zeitgeist.

But the Zeitgeist pushes back. When Gerber wrote a gripping student being psychologically, then physically murdered by insensitive peers, teachers and parents, he got some icy reactions. “Some parents were upset by the story because they said it was pandering to students, telling them that they are right and teachers are wrong. The point wasn’t that at all. The story said that teachers can be wrong.”

"People don't expect objectivity of Joseph Heller"

“I get these requests from greater objectivity. God, this isn’t journalism. It’s fiction. People don’t expect objectivity of Joseph Heller or Sallinger, but they do of comic book writers.” Gerber gestures, as if shaking a beach ball – or bomb. “We’re constructing a dramatic event, not reporting it. It’s fiction. Boom! People are expected to come to their own conclusions.”

Then he leans back, sighs. “It shows you the state we’ve reached: that people seriously believe a comic book writer can dictate opinions to them, that anybody can dictate opinions to them. They want opinions dictated, but mine simply run contrary to what they think, so they don’t want to hear them.”

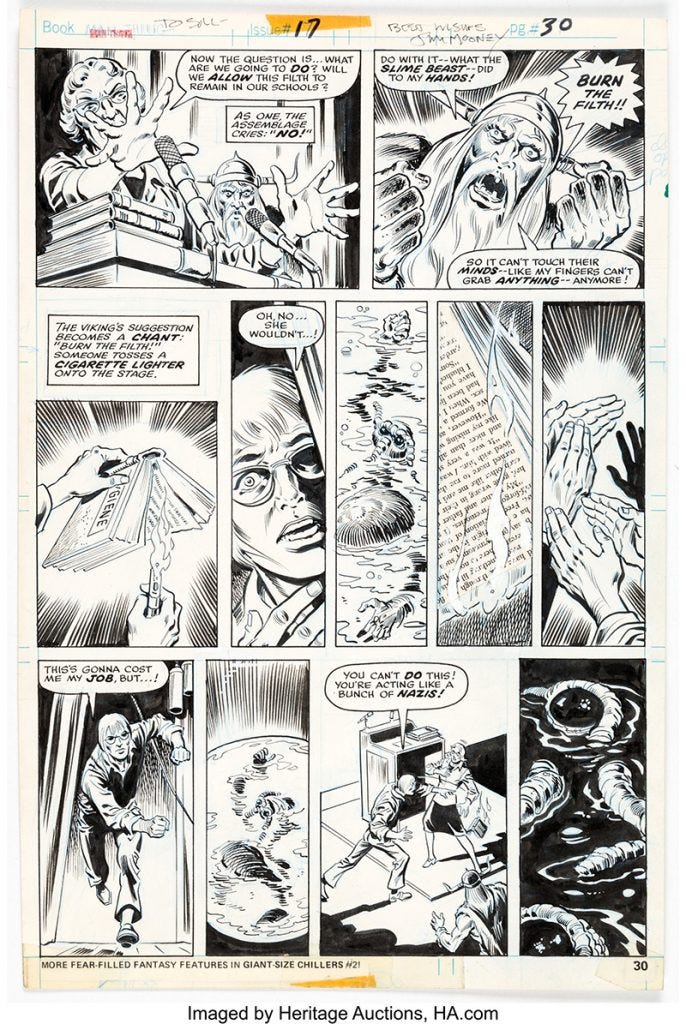

The closed-mindedness is a target for Gerber in his stories, as well. The swamp creature Man-Thing, which is without higher reasoning powers, can only sense emotions, and, in fact, feeds off them. The empathetic beast is internally prodded when he stumbles into a town obsessed with… book burnings.

“There are three or four times in the story (“A Book Burns in Citrusville,” Man-Thing #17, May, 1975) when the opportunity presents itself for those people to say, “Stop. We have gone too far.” They blow it every time. After the last opportunity – the death of the daughter of the woman who leads the burning – there was no place left for them to go but to burn the books. And in doing so, destroy themselves, actually.”

Gerber looks into his coffee for a long moment.

"The destruction of ideas = the destruction of humanity"

“I related the destruction of ideas with the destruction of humanity. That’s what they were really doing. That’s what they were afraid of in the first place.”

Gerber is one of a few comic book writers from St. Louis whose reputations have risen with the quality of their craft.

Roy Thomas was editor at Marvel Comics, Gerber’s base, where he would occasionally come up with a striking scene – such as an old man, a veteran of World War II and prison camps, telling a supehero “not to look for scars. They are all in the mind.”

Denny O’Neil works for Marvel’s competitor, DC Comics, and wrote the acclaimed Green Lantern series that strove for “relevance” before it become more common. An old man addressed the Green Lantern: “You’ve roamed the galaxy, helping green skins and blue skins. One thing I want to know is, what you’ve done on Earth – for the black skins?” The hero can’t answer.

Gerber, the latest St. Louis native to join those writers in New York, comics’ publishing hub, has gone so far as to actually set his stories in his hometown, St. Louis. The Son of Satan battles atop The Gateway Arch and over Forest Park, and the school seen controversial Man-Thing story is the physical replica of University City High School. (Gerber was voted “Funniest Boy” in U. City High’s Class of 1965.)

The people he’s known are, of course, reflected in the stories, as well. But St. Louis has never developed a superhero of its own, partially because Steve Gerber never writes about one.

"I've never met a hero"

“A hero, in a classical sense, it somebody who is usually in control of all situations, has no real major flaw in his personality. These people don’t exist! I’ve never met one. I’ve neve read about a real one, so I can’t write about one!”

“The problem with heroes and the image they give to kids is they don’t really question what they’re doing. Superman never stops to think, “Should I have ripped that mountain apart?”

Gerber’s smile returns, but he is very serious.

“What are the consequences of ripping that mountain apart? I don’t want to encourage kids to do that. Kids should be asking questions constantly. I think virtually all the characters in my stories do that.”

The characters who don’t stop and think are usually Gerber antagonists. The books burners. A mad Viking out to kill via axe all “sissy men.” Vengeful lovers. The Ku Klux Klan. And of course: the Devil.

On the other hand, there are sympathetic characters, often on the road to ruin nonetheless, including guilt-ridden advertising writers (with a touch of Gerber auto-biography there.) A housewife with no identity forced to run away from home at 35. And all the while: superheroes.

The fans – a nucleus of thousands of devoted comic book collectors and students of the media who absorb the work each month – like it a lot. They gave Gerber his “Shazam” Award.

It probably won’t be his last.

A Steve Gerber Scene:

Here’s the video version of this article!

Bonus #affiliate links: Steve Gerber on Amazon

Man--Thing by Steve Gerber: The Complete Collection, Volume 3

The Complete Howard the Duck Collection

Omega the Unknown Trade Paperback

Marvel Masterworks: The Avengers Volume 18

Walt Jaschek is a writer of comics, comedy and copy for big brands. For his work creating funny, award-winning ad campaigns for the entertainment industry, he was inducted in 2018 into the St. Louis Media Hall of Fame. Declaring "I'm not history yet," Walt is writing away on his original I.P. at last. Netflix gets first look.